The

“Beauté Congo” exhibit at the Fondation Cartier in Paris has been so successful

that it is extended until 2016. As I

walked through the exhibition, I noticed that most of the human subjects were men-

Congolese politicians, Barak Obama or Muhammed Ali, for example. The occasional woman

was provocatively dressed or a showcasing a car or pregnant with a budding male

writer/artist.

Then I noticed that the artist names on the wall were all male. This

is not unusual, in any part of the world.

According to the Guerrilla

Girls, in 2012 less than 4% of artists in the modern art section of the

Metropolitan Museum of New York were women. But in

2015, in a major art capital like Paris, at an exhibit representing an entire

country and spanning a century, at a venue that according to Cartier’s website,

“distinguishes itself by its curiosity, originality

and heterogeneity,” I hoped for better. In the WSJ, Tobias Grey, says the “show’s scope is

ambitious.” I wish it were ambitious enough to include women.

I asked

a girl working at the museum entrance if there were any women artists in the

exhibit. She nodded no, then as I walked away, she said: “Wait! There is one

downstairs.” I headed there, excited. Finally, towards the end of the

exhibition, I saw the name: Antoinette Lubaki. She was born in 1895. There were

4 works by her, identical in subject and style to the 14 works by her husband

nearby. So, I considered some of these possibilities:

1.

No

woman born in the 20th century, in this country of 77 million

people, ever touched clay or a brush, camera or other artistic tool or attended

an art school or produced anything of artistic value.

2.

The

curatorial team (headed by Andre Magnin), did not make an effort to look for

such a woman. It is noteworthy that of the 11 (mostly white) catalogue contributors,

only two- Nancy Rose Hunt and Dominique Malaquais, are female.

3.

Magnin’s

definition of what constitutes Congolese art is too narrow to include what

women do.

4.

For

any number of reasons (which might include economics, war and societal

expectations), women are discouraged from making art.

Magnin said, “It is my duty to recount…the

adventure that led me to a deep exploration of Congolese art. I had three aspirations with Beauté Congo.

The first…was to share with a Western public the passion that impelled me to

search all over Congo-Zaire for thirty years. My second aspiration was to tell the story of ninety

years of Congolese art which had always been described partially, and was

visually familiar, but only fragmentarily so until now. I want this exhibition to widen people’s perceptions of the country…”

Yet, I

still feel I am being presented a “partial” and “fragmented” story. One interesting

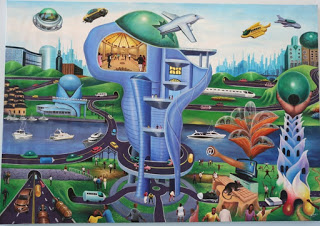

work is a painting whose title translates into “Africa of the Future.”

Here we see a

utopian vision of a modern world- clean, bright, and where women are mostly

invisible. The few women are accompanied by a man, while the men either walk

independently or with their friends, drive cars or spaceships. I counted

approximately 57 men and 9 women. This far exceeds the imbalance in countries

like India and China, which have a preference for sons and where (according to

the Daily Mail) “there are now as many as 120 or 140 boys for every 100 girls

despite a ban on gender-based abortion.”

Art reflects back to us our desires, values and

beliefs, so what is this painting saying?

I would have

liked the Fondation Cartier to address why, of the 350 works shown and of the

40 artists represented, only one is a woman (represented by 4 pieces, or 1.1%

of the total works). I am not even sure

1.1% is statistically relevant. The Guardian refers to this show as the “first

ever retrospective of art from the DRC”, but it would be more appropriate to

clarify for visitors that this is the first ever retrospective of art by MEN

from the DRC. In France, where people love to strike, why haven’t the citizens

of Paris plastered fliers or held signs in front of the Fondation? Why the

blindness and complacency? Of all the reviews I’ve read, only Rachel Donadio in

the New York Times has touched upon this, and brings in a quote by Pascale

Obolo regarding the “neocolonial and paternalistic attitude of Mr. Magnin.” Ms.

Donadio also informs readers about Michele Magema, a successful Congolese

artist who has exhibited internationally, yet wasn’t included in this show. How

did Magnin, “The world’s foremost expert on African art,” (according to The

Guardian) miss her?

Jenny Stevens, also from

The Guardian, interviewed one of the artists in Beauté Congo, Kiripi Katembo.

He shares his thoughts about one of his images: “Women

raise children, look after their husbands, and also go out to work and provide.

Yet men are still seen as the chiefs. When I look at this picture, I think

about all the work women do to serve the economy of Congo and their families,

but they get no respect. They are treated like machines, while men can do what

they like. I also think of my mother, who died last year. She worked in the

market, ran her own business, knitted and worked out in the fields, too. So I

called this image Move Forward as a way of saying thank you to women – because

they are the true power of my country, the people driving it forward.”

A Guerrilla Girl who goes by KAHLO said, “ How can you really tell the

story of a culture when you don’t include all the voices within the culture?

Otherwise, it’s just the history, and the story, of power.” In this exhibit we

have a story of the power of men, and a story of the power of France in its

former colonies. We have the story of who finances exhibits in the contemporary

art world. Cartier is

owned by Compagnie Financière Richemont SA, based in Switzerland and headed by

a South African: Johann Rupert. As of 2014,

Richemont is the second-largest luxury goods company in the world and Rupert is

the 2nd richest man in Africa, valued at over 7 billion dollars.

I wanted to find a different story about Congolese women artists and

after searching, I came upon this. In April 2014, Ugandan born curator Robinah Nansubuga curated

an exhibition in Kinshasa called Women Without Borders, and it included 19

artists from central and east Africa, including the DRC. She estimates that “only about 10-20 out of 200 or 300

artists in a university here are women. We wanted to understand why there are

so few, and what challenges are holding them back.”

Other links of interest: